Warning: Undefined array key "sharing_networks_networks_sorting" in /var/www/wp-content/plugins/monarch/monarch.php on line 3904

Warning: Trying to access array offset on value of type null in /var/www/wp-content/plugins/monarch/monarch.php on line 3904

La MaMa in association with Art2Action presents the debut of a spoken word and multimedia performance called Eleven Reflections on September, written, directed, and performed by Andrea Assaf. The performance explores a post-9/11 New York, and the Arab American experience as a whole living in such an era. The show will open tonight, and will run until May 17. Additionally, the project also includes an interactive installation at the Hi-ARTS gallery that has viewers reflect on what’s changed after 9/11. The exhibit is currently open, and will run until May 22.

Downtown Magazine recently had the chance to speak with Assaf, who not only wrote, directed, and organized the performance, but is also the Artistic Director at Art2Action Inc. Check our in-depth interview, and be sure to check out Eleven Reflections on September at the La MaMa First Floor theater.

Do you have any personal influences for the project?

Assaf: Suheir Hammad is the first artist who comes to mind, in terms of influences. In 2008, I had the incredible honor of directing her in a stage production titled breaking letter(s), based on her as-yet-unpublished writing that became the book breaking poems, a genius work which won an American Book Award in 2009. It was an extraordinary experience, spending intimate time with her poetry and her process, and I think it influenced me deeply. Our aesthetics are different, and many of the poems in Eleven Reflections on September had already been written, but directing that piece with Suheir gave me an opportunity to explore the relationship between text, media, and movement that continues to be of interest to me in Eleven Reflections.

I also have to acknowledge Dora Arreola, Artistic Director of Mujeres en Ritual Danza-Teatro, a brilliant director, choreographer and performer whom I’ve had the honor of working with, on various projects, since 2001. I have learned so much from her over the years, it’s hard to imagine how my work as a theatre artist would have evolved without her inspiring and highly disciplined influence, especially in terms of movement aesthetics, and the visual dimensions of directing. Dora is an exceptional artist, who brings a global vision to everything she does.

The collaborating artists who initially developed the stage production of Eleven Reflections…, particularly the musicians and especially Aida Shahghasemi, who’s been performing with me since 2011, have also influenced me and this work deeply. Aida is very special. Her voice has a purity that touches people, on a soul level, and it’s very moving — even to me, after all these performances together, I still feel very blessed to share the stage with her, every time. Her collaboration and commitment to this project, and the music she brings, has been a major influence.

Describe your thoughts upon hearing of the collapse of the WTC.

I didn’t hear of it, I saw it. In a rather unusual way. On September 11, 2001, I was in Washington, D.C., because I’d just accepted a new position with Animating Democracy (a program of Americans for the Arts), and I was in Washington to sign the contract, even though I would be working from New York. In fact, I had just moved back to my 13th Street apartment in NYC, in August 2001, after a year long internship with Liz Lerman’s Dance Exchange. So I was in D.C., in my former apartment, and I got a call from Americans for the Arts, saying don’t come in. When I asked why, they said turn on the news. I then became aware of commotion on the street, and looked out the window — where I saw crowds of panicked people walking away from downtown, and smoke billowing up from what turned out to be the Pentagon. I turned on the television, and just then, I saw the WTC buildings collapse. Live, I think. I was in complete shock. It was a moment of severe disorientation. I turned on the news, expecting to find information about what was happening in D.C., and instead I saw New York falling to pieces. I think it took me about 30 minutes to understand what was going on. Actually, the first poem of Eleven Reflections… expresses this sensation of disoriented shock.

You say your experience as an Arab American “changed overnight.” Can you describe this for us?

I was a racial enigma for most of my life. I grew up partly in the D.C. area, and partly in rural Pennsylvania, where there was no Arab American community to speak of. I also grew up with my mother’s white American side of my family, rather than my father’s Lebanese American side, so I was often assumed to be Italian (which I am partly), or Latina, or maybe East Indian, or Jewish. Even in Manhattan, where I’d lived since 1991, there was a kind of cosmopolitanism that seemed to defy categorization. So I was rarely identified as Lebanese or Arab American, I think largely because it was not an identity readily recognized in the U.S. lexicon of cultural diversity. But after 9/11, that literally changed overnight. Suddenly, I was Arab. The social assumption was suddenly, oddly accurate.

I was reminded, every day. I lived near Union Square, which, as I’m sure you remember, was a hot bed of demonstrations, memorials, reporters, police… Just trying to bring groceries home, I’d be accosted by a reporter thrusting a microphone in my face, asking, “Are you a Muslim?” At Penn Station, trying to buy a train ticket, I was asked to show my passport. At a national arts conference, a colleague talking about 9/11 pointed her finger at me, and said, “It could have been you!” I was “randomly selected” for inspection at airports five times in a row. And that continued for years. Routine security, they said, for everyone’s safety. But with public buildings full of armed guards in camouflage and flags on every subway car accompanied by an acute anti-Arab backlash, and George W. Bush’s declarations of endless war — I began to feel distinctly unsafe.

It’s amazing how quickly the winds of suspicion can change, how you can find yourself in a chill, or a gust. It was terrifying to feel that happen, in the 21st century — as if we’d learned nothing from history.

How do you think the world will look back on the events of the early 2000s?

This is an interesting question. I think much of the world already looks back on it differently than most Americans. Certainly, everyone sees it as a tragedy. The loss of so many lives, the trauma of 9/11, the fear and uncertainly that has haunted our national psyche for years after. I also believe most of the world sees the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and all the violence and horror that so many people in the Middle East are suffering through now, as a tremendous tragedy. Unlawful, irrevocable, unjust. And it isn’t over yet. You know, Eleven Reflections on September focuses mostly on an Arab American perspective, but I also do a lot of work with U.S. veterans, people who are in recovery from PTSD or other severe mental health diagnoses, because of or triggered by their military experience. The war isn’t over for them, either. People who’ve lived through war live with it for the rest of their lives, whether they’re civilians, refugees or soldiers. A retired U.S. military general recently told me that we’re not going to see the full affects of PTSD from the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan until 2030. And that’s regarding veterans who only spent a few years in war zones, imagine for those who are still living there. The tragedies are far, far from over.

How do you feel about the idea of performance being a way to heal tragedy and trauma?

Absolutely I think of this work as a way of healing tragedy and trauma. It is for me, personally; but also, I hope, for the audiences and communities that come to see it. In a way, Eleven Reflections… is a lament, a way for us to mourn the things we haven’t taken time to grieve yet, a space to cry and feel, and then discuss what we feel and experience with others, who may be different from us. And at the same time, it’s an opportunity to investigate hope, to explore together how we might imagine a more peaceful future. The healing aspect is in the expression, the release, the dialogue, the opportunity to share untold stories.

In general, I believe this is how performance works as vehicle for healing trauma. It gives us a way to express the unspeakable — whether that’s through narrative, or abstraction, music or movement, visual expression or group discussion. And through that process, to envision new possibilities, and to motivate each other toward that shared vision, once we find it. I have been working with individuals who’ve experienced trauma for many years — survivors of domestic violence or sexual trauma, military veterans, survivors of torture, young people who’ve lived through urban warfare in our cities. I have seen the healing affects of artistic process first hand, many times. It is undeniable to me.

What do you think of the perception of Arab Americans or the Islamic faith in general throughout the world?

Well, again, I think perspectives range greatly throughout the world. It’s important to remember that Islam is the fastest growing religion in the world today. Clearly, many people think very highly of it. And many people are terrified of it, whether that’s because they genuinely don’t understand, or have been greatly misled by the media, or because they’ve directly experienced the disastrous effects of what happens when religious extremists (of any religion) gain political or military power, or because they’re selfishly afraid of losing their own positions of dominance in the global scheme of things. As with any religion, however, fundamentalists do not represent the majority of folks, and we cannot treat the majority as if they are extremists. If we do, we’re operating out of prejudice, and the result is discrimination, if not outright oppression.

Arab Americans, and Muslim Americans, have been experiencing this acutely since 9/11, although that certainly was not the beginning point of anti-Arab or Islamaphobic sentiment in this country. Jack Shaheen’s documentary, “Reel Bad Arabs” does an exceptional job of illuminating the history of racist representations of Arabs in Hollywood film since its inception. But we’ve been living through a particularly intense wave of it in the early 21st century. My only hope is that the rise of an Arab American cultural movement, through literature, theatre, independent media and music, is a re-humanizing force in our national consciousness.

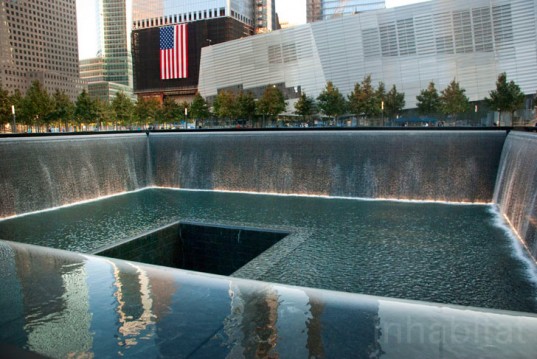

What do you think of the downtown Manhattan area now after 9/11?

I think it’s been rapidly gentrified. Certainly the East Village has, where my apartment is. I’ve been watching the development of the Memorial, and the construction of the new tower, from afar. I plan to spend some time there while I’m in New York. I think it’s important that we have a place to mourn and remember all the lives lost in the tragic events of 9/11. But I’m also very concerned and discomforted by the idea of disaster tourism. It’s disturbing to me that the memorial is on private property, rather than considered public property; and that it’s become an exercise in capitalism more than a space for spiritual reflection, or for the development of understanding, tolerance, and peace. I think it’s equally important that we remember not only the lives lost on that day, but all the lives lost in the thousands of days that have followed, and that continue to be lost, through our military actions in the Middle East–both soldiers and civilians.

Where do you see the area in the next 5-10 years?

I don’t know if I can answer that. I can say what I hope for: I hope it becomes livable again, in the sense of regular people being able to afford living here. I hope it balances out. I hope the wars and violent conflicts in the Middle East end, and that we put our militarism in check, and that lower Manhattan ceases to be a political excuse for that militarism. I hope that New York understands how we are intimately connected to these global events, and their on-going affects on real people. I hope that New Yorkers continue to say “Not in My Name,” as we did back in 2001-2003. And I hope Downtown New York is among the communities leading us to a more peaceful, more just world in next 5-10 years.

-by: Jackie Hart