Warning: Undefined array key "sharing_networks_networks_sorting" in /var/www/wp-content/plugins/monarch/monarch.php on line 3904

Warning: Trying to access array offset on value of type null in /var/www/wp-content/plugins/monarch/monarch.php on line 3904

There are times, especially in New York, that you encounter profound coincidences. This June, Brooklynites and synthesizer enthusiasts got to experience classic electronic music and to look forward to two very different futures for the synth world.

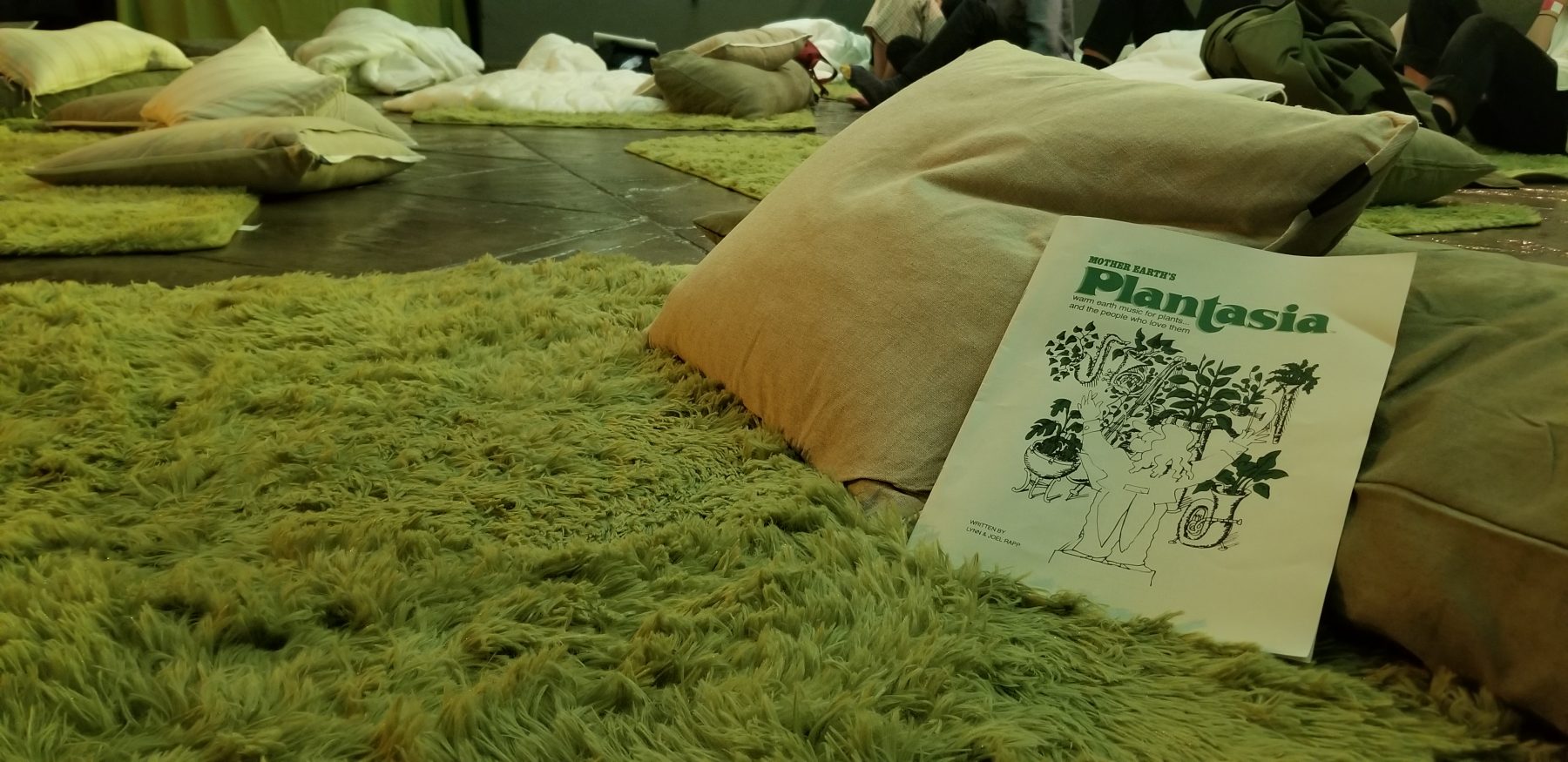

Last night, fans of plants, music, and niche cult oddities gathered at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden to experience a listening party for Mort Garson’s cult classic 1976 album Mother Earth’s Plantasia, aided by Atlas Obscura, which will be re-released this summer by Sacred Bones Records. The synthesizer-composed tracks are meant, according to Garson, to stimulate growth and well being in plants who “listen” to them. Plantasia was also one of the first albums ever composed entirely with a synthesizer.

The “listening” took place in the Garden’s conservatory, where two dozen soft green shag rugs had been laid out on the floor–looking not-accidentally like patches of grass–and covered in throw pillows. The crowd looked like what you’d expect for a listening party for a ‘70’s synthesizer soundtrack designed for botanical healing–that is, they looked like Brooklynites, but maybe a little more Woodstock-y.

As attendees lounged on the carpets and sat in chairs and listened, artist and biophilic technology designer Mileese explained some of the science and “science” behind Garson’s vision. The history of plant “intelligence” studies stretches back more than a century, with diverse experiments showing the plants’ receptivity to outside stimuli, music, and way more. Scientists measure and record the electrical data coming from the plants, trying to divine their thoughts. It turns out, plants like sex and classical music, aren’t fans of rock ‘n’ roll, and hate the evening news.

Meanwhile, just a couple weeks earlier, an entirely new generation of synthesizer stopped by our city. On June 8th and 9th, the Latvian visionaries of Gamechanger Audio visited the Brooklyn Stompbox Exhibit and Synth Expo to show off their latest invention: the Motor Synth, the world’s first synthesizer which generates sound with internal motors. For two days, more than 500 audio engineering tech enthusiasts stopped by to play with the Motor Synth, while three of Gamechanger’s co-owners –Didzis Dubovskis, Kristaps Kalva, and Ilja Krumins–ran demonstrations and took pre-orders.

“All the new advancements are usually in software stuff,” says Krumins, “So the industry is heading into software and we decided that we were gonna just disrupt everything and just say “There can be new analog instruments made, even in this day.”

As of right now, only three Motor Synths exist: two went with Gamechanger when they visited Brooklyn, and are now back in Riga; the third is in the capable hands of Jean-Michel Jarre, another pioneer who released his breakthrough synthesizer album Oxygène in France in 1976, the same year as Plantasia.

In some ways, the Motor Synth and its creators have a lot in common with the synth Garson used in 1976. Garson used a Moog Synthesizer, the first brand to sell synthesizers commercially. Created by Robert Moog in the early 1960s, they came into popularity as artists discovered the product throughout the decade. Garson himself discovered Moog in 1967 at a convention for the Audio Engineering Society.

Gamechanger Audio’s Motor Synth (Photo courtesy of Hummingbird Media)

Mort Garson’s Moog Synthesizer (Photo courtesy of Hummingbird Media)

It’s easy to recognize the shared lineage between the Moog and the Motor synth. The Moog is a multi-layer contraption covered in dials and buttons, while the Motor Synth has cut that down to a couple of dozen. They’re both black boxes, though the Moog comes up to your hip while the Motor Synth looks like it could fit in a generously-sized glove box.

It might be harder to see the common ancestor between the Motor Synth and Mileese’s grand finale at the Plantasia listening party. With a small garden of potted plants arrayed before her, all hooked up to wires and monitors, she explained that she had found a way to turn the “thoughts” of plants into music. She’d written a code which mimicked a synthesizer and which responded to changing biodata from the plants. She turned on the device and, more than 40 years after man used a synthesizer to serenade plants, the plants used a synthesizer to play back.

Mileese finished her performance and Mother Earth’s Plantasia began. Many left the room to explore the gardens as they listened. One woman wearing a hat made of rooster feathers–think like a feathery beanie–danced along with the music. Meanwhile, I wondered at two new approaches to electronic music, to synthesizer technology. In a two week spread, I was able to experience two separate futures to the fusion attempted by Garson in Mother Earth’s Plantasia: one sound drawn from spinning motors, the other from growing plants.